Market correction catalysts, plus U.S. immigration and the budget deficit

The Sandbox Daily (4.9.2024)

Welcome, Sandbox friends.

Today’s Daily discusses:

market correction catalysts

U.S. immigration

budget deficit

Let’s dig in.

Markets in review

EQUITIES: Nasdaq 100 +0.39% | Russell 2000 +0.34% | S&P 500 +0.14% | Dow -0.02%

FIXED INCOME: Barclays Agg Bond +0.34% | High Yield +0.21% | 2yr UST 4.743% | 10yr UST 4.362%

COMMODITIES: Brent Crude -1.03% to $89.45/barrel. Gold +0.91% to $2,372.5/oz.

BITCOIN: -3.62% to $69,122

US DOLLAR INDEX: -0.04% to 104.101

CBOE EQUITY PUT/CALL RATIO: 0.64

VIX: -1.38% to 14.98

Quote of the day

“You cannot swim for new horizons until you have courage to lose sight of the shore.”

- William Faulkner, Writer

Market correction catalysts

Piper Sandler’s Macro Research team released a report trying to explain 60 years of market corrections – ultimately to understand the fundamental drivers that underpin corrective phases and offer clues to help investors in the future. It’s a fascinating report that I’ll succinctly summarize here.

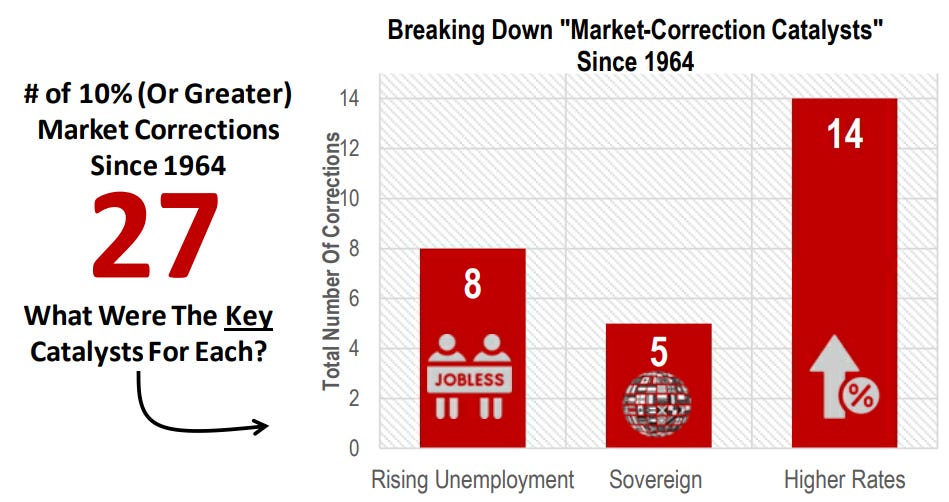

There have been 27 market corrections of 10% or greater since 1964.

Piper Sandler argues every single one had at least one of three main catalysts: 1) higher interest rates; 2) rising unemployment; or 3) a global (exogenous) issue. Obviously, we will sidestep the secondary and tertiary catalysts that accompanied each drawdown because markets rarely, if ever, move based on “one” variable.

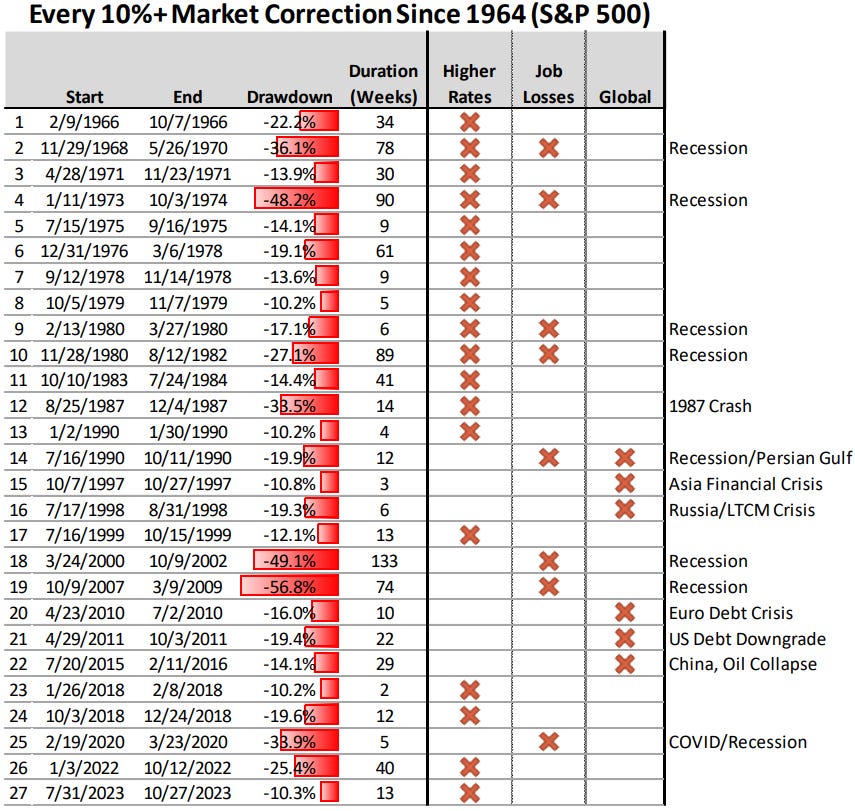

In the table below, all 27 market corrections are tagged by start and end dates, magnitude of selloff, duration, and primary catalyst:

You can clearly see that most employment-related corrections are long in duration and fall into the classic definition of a bear market (-20%+); in fact, all instances are accompanied by a recession. A sharp rise in initial claims tends to be what takes down the market in recessionary periods. How sharply the market falls and how long the pullback lasts depends on many factors including the severity of the job losses and how quickly the government/Fed steps in with stimulus measures.

In contrast, market corrections that are explained by higher interest rates are far more common with less severe declines over shortened periods of time. Higher rates were a contributing factor to all of the market downturns in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. The dynamic shifted in the 90s and 2000s as a structural decline in rates and zero interest rate policy (post GFC) largely neutralized the threat from rate markets.

Lastly, market corrections resulting from global issues (i.e., Long-Term Capital Management and U.S. debt downgrade) average around a 15% drawdown and tend to be even shorter in duration.

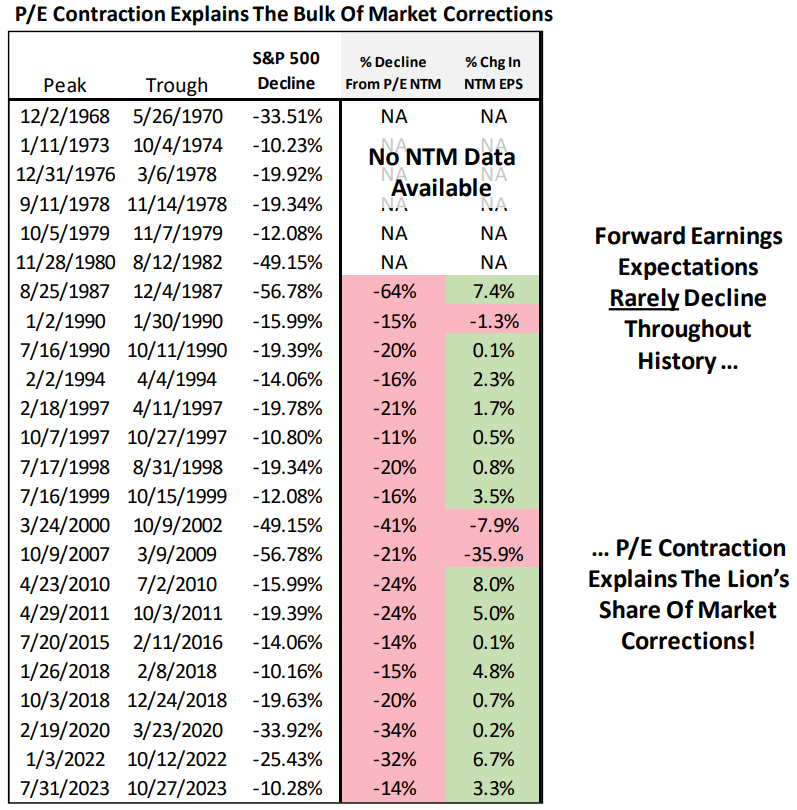

One other takeaway from this exercise stands out: market corrections come more from fear (multiple contraction, or P/E) than earnings.

The age-old joke about the stock market “pricing in” 9 of the past 5 recessions overlooks the fact that stocks can decline for a myriad of reasons, all that have little to do with imminent recession risk.

Valuation changes are essentially changes in investors’ perception of risk. Most market corrections since 1964 are NOT due to rising recession risks (i.e. jobs and EPS) but higher interest rates!

Source: Piper Sandler

COVID retirements and workforce exits nearly crippled the U.S

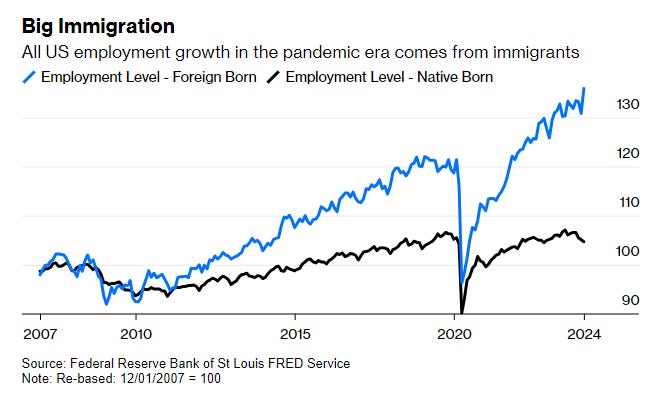

If not for positive U.S. immigration, the U.S. economy would have been significantly impacted by labor imbalances and wage inflation the last four years. As a result, America now has one of the strongest economies in the world.

Big influxes of new legal migrant workers can ease tight labor market conditions and the risk of a damaging wage-price spiral by giving employers a greater pool to recruit from.

At present, it looks as though labor shortages would feel severe (and hence the upward pressure on wages and prices would be more intense) if it were not for a sharp increase in the number of foreign-born workers looking for a job.

The figure of native-born workers in employment is still slightly below the level from the eve of the pandemic, while employment of the foreign-born has increased by more than 10%.

Don Rissmiller, chief economist at Strategas Research Partners, points out that the United States has been “significantly boosted by additional labor supply” and that this has offset ageing demographics. He adds: “This could be a politically unstable path (especially given the U.S. election in November), but it counts as growth in the meantime. ‘Big immigration’ helps explain the resilience of US activity against the backdrop of more sluggish economic data abroad.”

Source: Bloomberg

Does anyone care about the budget deficit?

I get asked a lot whether anyone inside or outside Washington D.C. cares about the deficit.

The United States federal budget is insanely complex due to the patchwork of legislation passed over many decades, multitude of spending categories and revenue sources, and competing political interests sprinkled across the top.

At the heart of matter is deficit spending, a labyrinthian concept which persists due to entrenched ideological divisions, reluctance to cut entitlement programs or raise taxes, and the prioritization of short-term political gains over long-term fiscal responsibility.

Addressing the deficit requires difficult decisions that often face opposition from various stakeholders, hindering short- and long-term progress. Additionally, structural factors such as entitlement spending and interest on the national debt compound the challenge. Political gridlock and partisan polarization further obstruct efforts to enact meaningful fiscal reforms, perpetuating the cycle of deficit spending.

In short, we kick the can down the road because we can. It’s politically untenable to address today. One day – a long time from now – the day of reckoning will arrive, but that’s for another generation.

The pie charts below show where the money goes and where the money comes from.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

That’s all for today.

Blake

Welcome to The Sandbox Daily, a daily curation of relevant research at the intersection of markets, economics, and lifestyle. We are committed to delivering high-quality and timely content to help investors make sense of capital markets.

Blake Millard is the Director of Investments at Sandbox Financial Partners, a Registered Investment Advisor. All opinions expressed here are solely his opinion and do not express or reflect the opinion of Sandbox Financial Partners. This Substack channel is for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. The information and opinions provided within should not be taken as specific advice on the merits of any investment decision by the reader. Investors should conduct their own due diligence regarding the prospects of any security discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information. Clients of Sandbox Financial Partners may maintain positions in the markets, indexes, corporations, and/or securities discussed within The Sandbox Daily. Any projections, market outlooks, or estimates stated here are forward looking statements and are inherently unreliable; they are based upon certain assumptions and should not be construed to be indicative of the actual events that will occur.